link to article

I See Hawks in LA

Here is something of a dirty secret about me: I love country music. And I’m not ashamed to admit it.

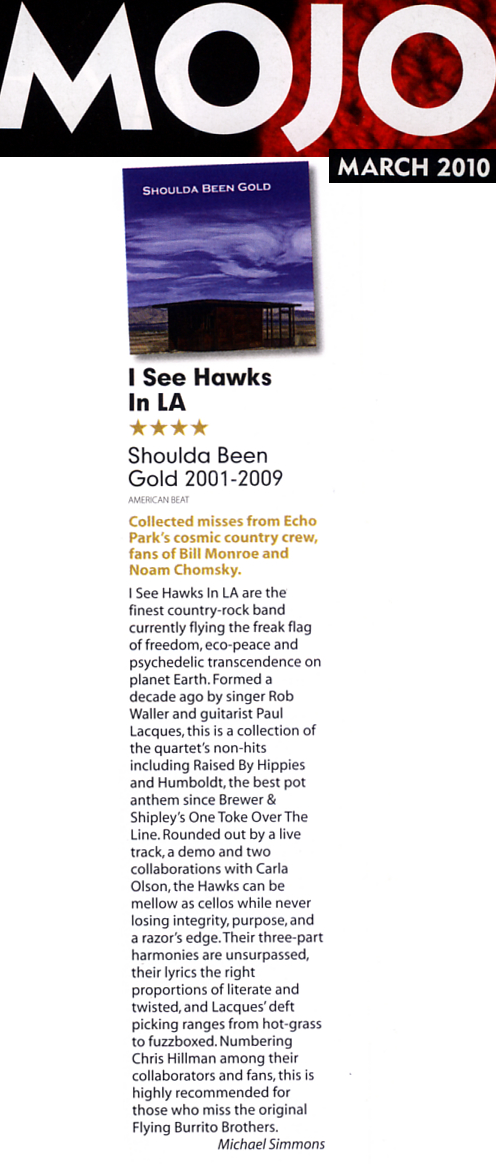

In fact, I feel that I can, with at least a little authority, proclaim that one of the best country bands in California (hell, in the world) is I See Hawks in LA, co-led by my friend Rob Waller (the band’s lead singer, rhythm guitarist, and contributing songwriter). Waller and I met in grad school, where we both taught in USC’s freshman writing program. We started our respective groups at roughly the same time, and even played a quirky double-bill together at Hollywood’s version of the Knitting Factory (referenced in the discussion that ensues below). Later, occasional Hawks collaborator Joe Berardi played in the IJG for a short time (long enough to hold down the drumming duties for our Industrial Jazz a Go Go! album).

After I left USC, Waller and I stopped running into each other regularly (except for that one time our two bands, heading in opposite directions through the heart of California, happened to stop, mid-tour, at the same rest-stop on the 5 freeway). But with social media, none of us are ever really out of touch, I guess. At least, that was how I learned that the Hawks had released their fifth album, Shoulda Been Gold — a “best of” compilation, but one that also included several new tracks (as well as a few rarities). I thought the occasion was a perfect opportunity to have an email conversation about this great band, and music in general.

If you’ve never heard the Hawks, here’s a good place to start.

* * * * *

Durkin: Though at first blush it probably appears to the outsider that there could not be two genres more divergent than jazz and country, we’ve joked in the past about possible points of resonance too. A music historian might mention the existence of folks like Bob Wills, or the musical roots of someone like Charlie Haden, or even Sonny Rollins’ cover for the Way Out West album. But I’m thinking too of deeper connections.

For instance: anyone playing jazz today has to deal somehow with the notion of authenticity. The music now has a history, a “tradition,” and a scholarship, and it is understood that each new generation of artists has to respond to that in one way or another (by fulfilling, tweaking, or rejecting certain expectations).

I could be wrong, but it seems like modern country musicians are faced with a similar dilemma. The music’s conventions are so well established that it must be hard for a young artist to maneuver without seeming to be derivative, or else too self-consciously “weird.” Plus, with country, you have that whole “Heartland of America” image to contend with. (Am I wrong in assuming that some audiences take that very seriously?)

Is this minefield real for you? Is it a minefield at all? And if so, how have the Hawks navigated it so elegantly?

RW: Ah, yes. “Jazz and Country, Together Again.” I remember our Jazz and Country night at the Knitting Factory in LA some years back. If I remember correctly it went pretty well, our crowds weren’t as divergent as we might’ve expected. But then we worked together and had some of the same friends. But yes, on to your question.

Authenticity is a major goal for us. It’s something we aim at. The problem is that it’s a moving target. Or, perhaps we’re the ones who are moving and the target is getting farther away. I have a suspicion that it is getting more difficult to make authentic music today in any genre precisely because of the accumulation of recorded music (not to mention all the scholarship, ‘zines, websites, listeners, authorities, etc.). There’s so much music to listen to and be influenced by it’s more difficult to just play it and feel it spontaneously, light-heartedly.

We’ve had the ability to record and reproduce music now for a little more than one hundred years. That’s really not that long compared to the history of music. I imagine that if you stumbled upon some band playing music in 1850 you would be thrilled, you’d grab your friends and bring them over, you’d sit dumbfounded and delighted as you watched and listened to them play. But now music is everywhere, in the elevator, on the radio, at the grocery store, stacked in gigabytes in your computer. Its value has shrunk to zero, basically. Music is now free because it’s everywhere and there’s no need to actually pay for it. This is a real problem for musicians who take years to develop their craft.

Oh shit, I’ve gotten away from the question and headed into a bitter rant against technology once again. Sorry, let me get back to your question….

Yes. The answer is yes, it is a minefield but a minefield is only dangerous if you walk into it. And pretty much we haven’t. It’s more like, “Hey, there’s a nasty minefield over there. Fuck it. Let’s go in the opposite direction.” Luckily we’ve had a group of people who has been interested and supportive of going with us. We take the things we love from the tradition, vocal harmonies, song structure, melodies, a connection to the earth, freak or outsider status (yes, even that is part of the tradition) and ignored the rest (bogus patriotism, xenophobia, trucks, mama).

Durkin: As one who is interested in freak / outsider status, I’d love to hear more about the freaks and outsiders of country music. Because that’s not really part of the general perception of country music, as far as I can tell.

RW: One of my favorite aspects of country/folk music is precisely that freak, outsider, drunk perspective. My favorite country artists (Merle Haggard, George Jones, Johnny Cash, Stanley Brothers, Louvin Brothers) are always flaunting their flaws. Whether it’s alcohol or being poor or being a criminal or turning your back on Jesus, the theme is often confessional and by association outsider. Here is who I am, here is what I’ve done, who I’ve killed, etc. I am guilty!

I first started getting into this music when I started dating my future wife. At the beginning of our relationship she made me a tape of murder ballads. Songs like “Katie Dear” or “Knoxville Girl” by the Louvin Brothers or “Pretty Polly” by whoever wrote that. These songs really got me and that’s when I started writing in this tradition. David Allen Coe and Johnny Cash played shows in prisons and related to prisoners because they had been prisoners. It was a genuine connection. When you listen to Live at Folsom Prison, Johnny is one of them. He’s not patronizing or clowning, he really feels for their circumstance and knows he might end up back there. He’s a freak and a fuck-up too.

To me, classic country and folk often maintained a legitimate connection to real people and real problems. Of course, that’s all pretty much gone from mainstream country now. It’s mostly about the girls getting wild on Saturday night, kicking Osama’s ass, and bullshit nostalgia for calculated, phony family values. It’s not just the connection to real people that’s been lost but the people themselves have become disconnected from their own reality. We’re a nation in denial of how bad we have it, how bad we feel. We can’t even properly imagine our own lack of freedom, our own cultural poverty, our own pain. We don’t have the words for it. We can’t even describe the pickle we’re in. In much of the heartland including Minnesota where I grew up, any hint of dissatisfaction is somehow unpatriotic, whiny, and liberal.

Durkin: As a fellow leader-of-a-ten-year-old-band-sans-hits, I’d love to know more about the Hawks’ adventures in the modern music industry. Ten years ago I seem to recall all sorts of exciting predictions about how we were entering a new age, in which independent musicians would use the tools of the digital era to storm the corrupt citadels of the music business. (Okay, maybe I’m exaggerating a little.) Looking back, having survived the decade with a working band, what did you learn about how things actually went down? And where do you fall on the despair / hope continuum when it comes to the future of music? Is Twitter going to save us all?

RW: No, we are not going to be saved by Twitter. We are all going to die. But this is not a hopeless statement. It should be a galvanizing one. We are going to die! We are most likely not going to be rich or famous or even have health insurance. But so what? Everyone on the planet is going to die, the vast majority of them poor and unknown. And all of us are going to attempt to create meaning in our lives. By having families, jobs, growing plants, going to church, doing yoga, eating well, whatever. One of the main ways I create meaning in my life is by making music that I think is good according to my own twisted aesthetics. Ultimately, it’s a spiritual practice. I do it with daily regularity to sustain meaning, to keep going back to that place where the muse lives, to avoid loneliness, isolation, CNN. But I don’t want to minimize it and make it sound like a hobby. It’s not. God, I hope music is never my hobby! It’s my spiritual practice, identity, source of inspiration and meaning.

Durkin: That’s great. I completely relate. It’s interesting that most of the people I admire in music these days have some sort of “second job” to support what they do — but I also think most of us aspire to be able to play music without having to worry about that distraction. And yet maybe making music into your “career” would kill the very things that attracted you to it (spiritual practice, etc.).

RW: Yes, the tension between day job and music career is ongoing. In that same spirit of contradiction, they do often each make the other possible. I suspect that if I quit my day job altogether, I might be more likely to make more mainstream music, or play more covers, or play more weddings, or be more concerned with being timely and hip. The fact that I keep a day job which provides for me and my family also helps to maintain artistic freedom and integrity, I think (hope). My family’s next meal does not depend on the song I’m writing.

Or maybe it just makes me lazy. I also wonder if the day job allows me to be too complacent, too comfortable being a freak, an outsider, an obscure toiling artist. Maybe I’d write better songs, more urgent songs, if I didn’t have any safety net whatsoever. It’s difficult to know the answer precisely.

Durkin: What was the selection process for including the previously released material on the new album? Were there any hard choices? Did you feel like anything got left out?

RW: Okay, an easy one. We went to the iTunes store and sorted all our songs by popularity then picked the tops ten songs. We wanted to let the fans decide and also avoid having a big band fight. We then added 5 new tunes, and a couple of curiosities for our die hard fans. If I had decided the list myself it would’ve been different but not that different. We do plan on a SBG: Volume Two down the road so there will be another opportunity to gather some of the left out tunes.

Durkin: The new album, from the title on down, is steeped in metaphors and images of despair, missed possibilities, promises broken. And yet you keep coming back to hope too. The upbeat protagonist in “Raised by Hippies,” the salvation of someone like Robert Byrd, the beautiful melodies and harmonies of “Laissez Les Bontemps Roulet,” all suggest an underlying belief in the possibility of redemption and happiness, even if bittersweet. Is there a coherent philosophy tying these extremes together? Or: as a thoughtful person making thoughtful music in a thoughtless age, how do you cope?

RW: I’m not sure how coherent the philosophy is but there is one. Even our band name is a metaphor. Here in Los Angeles, this concrete metropolis of monoculture, there is still wildlife (hawks, coyotes, skunks, possums, hummingbirds, the occasional condor) there are are still strange country rock bands like ours even though we don’t get the kind of attention that say, Britney Spears or some other pop star gets. Yes, on a grand scale things are a bit hopeless. The earth really is headed for an environmental catastrophe. The political system and the economy really have been hijacked by the obscenely wealthy. These are troubling times and the problems are so big it’s overwhelming.

But life goes on. Children are born and they shine some light in, some optimism. The hopelessness and the optimism exist side by side. I take some refuge in my own personal contradictions. I’m an environmentalist but I drive a GMC Yukon. I’m a country rock musician and lead singer who wears flashy outfits onstage but I’m also a mild-mannered writing instructor at a university (a job I compare to working in a convent, fashion and other-wise). I’m a parent but I’m still fairly reckless at times when it comes to money and planning for the future. I guess the thing that holds it all together is a belief in the grand life cycle of it all. Things will be born, hopefully thrive for some period, then die. Then something else will be born. In this way, I welcome the coming apocalypse.

Durkin: We’re both dads, and in our art, if not our lives, we’re both a little wry. I don’t think either of us is predisposed to sugar-coating. And yet children, to some extent at least, inevitably require at least a little sugar-coating in their initial understanding of the world.

How do you reconcile these things? How does fatherhood coexist with the hint of nihilism, the vaguely apocalyptic strain that runs through your music? Do you play your music for your kids?

RW: Yes, I sure do play my music for my kids. They also know lots of the songs and sing along. My daughter Zola (5) came on the road with us to Scotland at one and a half. She still likes to sleep in my guitar case. For about six months she listened to one of our albums (Hallowed Ground) every night as she fell asleep. She knows the songs inside out. We recently played a show in Santa Barbara at a coffee house type place and there was a couch on stage behind the drums. Both Zola and her brother Henry (almost 2) danced around for a while then passed out on the couch for the rest of the show, sleeping right there on stage. That’s how it’s gone. Some of our tunes are fairly dark and require some censorship or explanation but overall there is a great deal of joyfulness present in music and the act of making the music that children pick up on the most. We’ll see how it all turns out as they get older. But I do see a real creative spirit in both of them that I take some credit for and that I think will continue to develop. I’d be surprised if they ended up as nihilistic and apocalyptic as their old man just because their lives and experiences are inevitably going to be so much different than mine. Again, I guess I see the apocalypse as a good time!

Cross-eyed hawks: it’s too bad they don’t have a sense of humor.

Durkin: What is the unlikeliest thing (musical or otherwise) you have been inspired or influenced by?

RW: I think my wife’s cooking has really influenced me as an artist. She’s an amazing cook. She develops new techniques, explores unusual ingredients, takes her time and develops her craft but it is all done in a loving way that’s about nurturing and feeding her family. I hope I can do the same with my music. Often, the dough I do make at gigs, etc goes right to the grocery store and turns into breakfast, lunch, and dinner. That’s a good feeling.

Durkin: Can music be effectively “political” (i.e., can it really matter, politically) in 2010, with its 24-hour hyper-media-with-a-vengeance vibe? Do you want the Hawks’ music to be political? And if so, how do you know the difference between offending somebody (I’m thinking of the dropped line from “Humboldt”) and educating them? [Editor’s note: “Humboldt” originally ended with the line “You can have your September 11 / I’m heading off to a Stoney Heaven.” According to the liner notes for Shoulda Been Gold, “when we sang the line in summer 2002 at Galapogos club in Brooklyn and the Knitting Factory only a stone’s throw from the twin towers site, we could see a moment of hurt bewilderment sweep through the audience like a slap in the face. We dropped the line.”]

RW: Hmm, not sure I have a good answer to this one. I guess music can be sort of political but I don’t really expect it to change anything in any direct way. So, not too effective. I think the Hawks are a political band in many respects (particularly with regards to the environment) despite the fact that as a band we have diverging view points.

The Humboldt line change was an interesting phenomena. We definitely lost a few fans and one writer in particular who had written glowingly about us before really turned on us because of it. Part of the reason the line was changed (which we didn’t mention in the liner notes) was I thought it might date the song too much to include September 11th. I don’t know if I was right about that since 9/11 has become a permanent thing, also we kept the Bush line which also dates it but I just didn’t have a good substitute for that one. “I quit my job at the 7/11” also seemed to fit the narrative of the song a bit better. Mostly, I think for myself as the the lead singer (the one singing the line) I didn’t want to reflect on that event over and over every time we played that song. The song is kind of our big closer and it’s a pot anthem that’s mostly just about rocking out and having fun. The political element seemed out of place, somewhat. It also seemed cold and unfeeling to those who really did suffer on that day. Also, our libertarian bass player never said anything about it but I knew it was eating at him. His son is in the Air Force in the desert. The personal outweighed the political in that sense and that also lead to the line change. Who knows, maybe it was big mistake.